In those years, the Western Wall did not have the large plaza we know today. There was a narrow alley for the Jews to pray, squeezed between the sacred stones of the Kotel and the Arab houses of the Mughrabi Quarter.

The British Mandatory government had imposed strict regulations, forbidding even the smallest sign of permanent sanctity. No Torah ark. No tables or benches. Not even a stool. The Jewish worshippers who gathered in the alley faced rules that seemed designed not just to limit their physical space, but to humiliate them at the very heart of their faith, at their holiest place of worship.

The prohibitions ran deep. Jews were forbidden to pray aloud, lest their voices disturb the Arab residents living nearby. Torah readings were exiled from the Kotel to the synagogues of the Jewish Quarter, as if the word of God could not be voiced at His most sacred site. And the sound of the shofar — symbol of Israel’s redemption and sovereignty — was silenced on the holiest days of the Jewish year. British policemen stood watch, enforcing these edicts with cold efficiency.

Give Me a Shofar!

It was Yom Kippur, 1930. I was standing among the worshippers at the Kotel, the air thick with the solemnity of the day. Between the Musaf and Minchah prayers, I overheard whispered conversations. “Where will we go to hear the shofar?” someone asked. “It is impossible to blow here. The police are everywhere — more of them than us…”

Even the police commander was present, to make sure that the Jews would not, God forbid, sound the blast that marks the close of the fast.

As I listened, a quiet resolve began to stir within me. Could we truly allow the shofar to be silenced? The shofar that proclaims God’s sovereignty over all creation? The shofar that blasts out the promise of Israel’s redemption? True, the custom of blowing the shofar at the end of Yom Kippur is just that — a custom. But a Jewish custom is Torah!

I approached Rabbi Yitzchak Horenstein, the rabbi of our ‘congregation’ and said quietly, “Give me a shofar.”

“What for?” he asked, his eyes narrowing.

“I will blow the shofar.”

His gaze flickered toward the policemen standing nearby. “What are you talking about? Don’t you see them?”

“I will blow,” I repeated.

Rabbi Horenstein turned away abruptly, but not before casting a quick glance toward the prayer stand at the end of the alley. I understood his unspoken message: the shofar was inside the stand.

As the time for blowing the shofar approached, I moved toward the prayer stand. My heart raced. I leaned casually against the stand, my fingers finding the drawer. Quietly, I opened it and slipped the shofar beneath my shirt. It was mine now. But what if they saw me before I had the chance to blow?

I was still unmarried at the time, and following the Ashkenazic custom, did not wear a tallit. I turned to the man praying beside me. “May I borrow your tallit?” I asked, my voice low but urgent. He looked at me with confusion. My request must have seemed strange to him, but the Jews are a kind people, especially at the holiest moments of the holiest day. Without a word, he handed me his tallit.

I wrapped the tallit around me, feeling its warmth and protection. Beneath its folds, I felt as though I had created my own private domain. Outside, a foreign government prevailed, ruling over the people of Israel even on their holiest day and at their holiest place, and we are not free to serve our God. But under this tallit, I was under no dominion save that of my Father in Heaven. Here I shall do as He commands me, and no force on earth will stop me.

As the congregation reached the final words of the Ne'ilah prayer — “Shema Yisrael,”

“Blessed be the Name,” “The Eternal is God” — I took a deep breath.

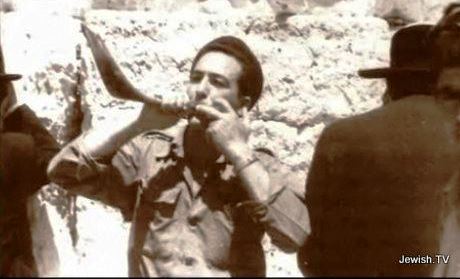

With one swift motion, I lifted the shofar and blew a long, resounding blast that echoed against the ancient stones.

Arrest and Release

Chaos erupted. Hands grabbed me from every direction. I removed the tallit from my head and found myself face to face with the police commander. His expression hard, he barked: “Arrest him.”

They led me to the Kishleh, the old prison in the Old City, where an Arab policeman was stationed to watch over me. Hours passed, the hunger from the fast gnawing at my insides, but I was given neither food nor water. I waited in silence, unsure of what fate awaited me.

Then, without warning, at midnight, the policeman received his orders. Without a word, he opened the gate and released me into the night.

As I stepped into the cool air, I was met by a group of young men from Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav.

“My friends!” I called out to them. “What are you doing here at this hour?”

They explained that, as soon as the shofar had sounded, they had rushed to tell Rav Kook what had happened. The chief rabbi was overjoyed to hear that the shofar had been blown at the Kotel, but saddened to learn of my arrest.

All this took place before Rav Kook had broken his fast. He did not eat, but on the spot called the High Commissioner’s office, demanding my immediate release. When his request was turned down, Rav Kook informed the secretary that he would not break his fast until I was freed. The High Commissioner resisted for several hours; but finally, out of respect for the chief rabbi, he had no choice but to set me free.

For the next eighteen years, until the Arab conquest of the Old City in 1948, the shofar was sounded at the Kotel every Yom Kippur. The British understood the power of that sound. They knew that it would ultimately break their hold over our land, just as the walls of Jericho had crumbled before Joshua’s shofar. They did everything in their power to prevent it. But every Yom Kippur, the shofar was sounded by brave men who knew they would be arrested for their part in staking our claim on the holiest of our possessions.

Postscript

Rabbi Moshe Segal’s story did not end in 1930. Immediately after IDF paratroopers liberated the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967, Segal arrived at the gates, determined to take up residence there. The soldiers on guard were reluctant to allow him in, explaining that they could not take responsibility for his safety.

Segal replied that he relied on a Higher Power for his safety.

“We have received a gift from God,” he exclaimed. “Do you really expect me to remain outside?” Ultimately, he was escorted through the streets with an armored jeep. It was inconceivable to him that Jerusalem should be reunited without a single Jew living in the Jewish Quarter.

That Yom Kippur, Rabbi Segal returned to the Kotel. This time, as the fast drew to a close, he blew the shofar, sounding its triumphant call of redemption, without fear of arrest by British policemen.

Rabbi Moshe Segal passed away in 1985 — on Yom Kippur, the day that had marked such pivotal moments in his life. Like Rav Kook, Rabbi Segal was laid to rest in the ancient Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, overlooking the city he loved so dearly.

(Adapted from Yanki Tauber’s article posted on Chabad.org. Additional notes from An Angel Among Men pp. 220-221; “The Man Who Sounded the Shofar” (In Jerusalem, Greer Fay Cashman, 5/10/2007).

See also: The Outlawed Shofar Blower.