One of life’s most profound questions concerns the true significance of our actions. While the performance of mitzvot and acts of holiness is undeniably meaningful, uncertainty arises regarding the value of our everyday activities.

Ultimately, how much of our lives and pursuits truly matter?

39 Categories of Melachah

The Mishnah (Shabbat 7:2) enumerates 39 categories of melachah — activities prohibited on the Sabbath, such as planting, cooking, and building. The Talmud in Shabbat 49b presents two possible sources for these 39 categories:

In fact, the word ‘melachah’ appears 65 times in the Torah, but the Sages limited their count to verses directly connected to the Sabbath or the Tabernacle. This led to occasional disagreements regarding which verses qualify. One of the verses in question describes Joseph’s work for his Egyptian master, Potiphar: “And he came to the house to do his work (melachto)” (Gen. 39:11).

Why should this verse be included in the count? Surely it has no connection to the Sabbath!

The Completed Realm of Shabbat

We must first analyze the two views presented in the Talmud, which relate the 39 categories of activity either to the construction of the Tabernacle or to the word ‘melachah’ as it appears in the Torah.

The Sabbath day of rest stands in stark contrast to the weekdays, which are filled with activity and labor. While the weekdays reflect the ongoing work of creation, the Sabbath foreshadows the universe’s ultimate state of completion, when all activity is finished. Work, by its very nature, implies incompleteness, whereas Shabbat offers a foretaste of olam habah, the perfected and complete World to Come.

We live in an unfinished world of preparations and labor. The Tabernacle was a center of holiness within a spatial framework, subject to the limitations of our incomplete world. God’s command to build the Tabernacle required that all categories of activity be channeled in its construction. The Jewish people needed to overcome the obstacles of mundane activities that hinder elevated life. Building the Tabernacle enabled them to attain their ultimate objective, a life of holiness and closeness to God.

The second opinion is rooted in a higher perspective. The division between the sacred and the profane only exists within our fragmented and incomplete reality. But when all actions bring us to a single, elevated center, when all of life is directed towards its true purpose, the distinction between holy and profane disappears. All aspects of life are bound together in the lofty union of kodesh kodashim, the Holy of Holies.

Through this higher lens, all activities become connected to the Sabbath ideal. The view that sees in every verse that mentions ‘melachah’ as relating to the Sabbath is not satisfied with ascribing meaning and significance only to that which is kodesh, only to those activities associated with building the Tabernacle. This inclusive outlook encompasses both the holy and the profane, seeing all activities elevated with the holiness of the Sabbath. Not only is the holy center elevated, but also the branches — all forms of ‘melachah’ as recorded in the Torah.

In short, these two opinions deliberate our original question. The Talmudic discussion regarding the source for the count of ‘melachot’ is, in fact, our question of how much of life truly ‘counts.’ Are only holy activities truly meaningful? Or is there eternal significance even in other areas of life?

Labors in Foreign Lands

According to the second, more inclusive view, the Sabbath encompasses all activities of the Jewish people, both past and future, both personal and national. However, the Jewish people in their long history have expended much time and energy in dispersed directions. Many Jews used their talents to serve alien agendas. This is the essence of the Talmud’s doubt regarding Joseph’s labors in Egypt. Can labors performed in foreign lands for alien goals still be counted as part of the accumulated service of the Jewish people over the millennia? Do such actions hold eternal value?

On the one hand, it is inconceivable that the labors of a Jewish soul will not carry some residual imprint of the Jewish nation. Even if it was ‘planted’ on foreign soil, that which is suitable can be added, after removing the dregs, to the treasury of elevated Sabbath rest that Israel will bequest to itself and the world.

On the other hand, labor that was performed under foreign subjugation and enslavement is perhaps so far removed from the spirit of the Jewish people that it cannot be incorporated into the collective treasure of Israel.

Joseph’s Labors under Potiphar

According to the Midrash (Tanchuma VaYigash 10), Joseph embodied the entire Jewish people. Even as a slave under Potiphar and a prisoner in Pharaoh’s dungeon, his labors were imbued with Divine blessing and success: “His master realized that God was with him and that God granted him success in all that he did” (Gen. 39:3).

Nonetheless, we should not forget Potiphar’s position as Pharaoh’s chief executioner. Joseph’s work for Potiphar was certainly alien to the spirit of Israel. Could the inner blessing of Joseph’s labors under such conditions be added to the treasury of activities connected to the perfected realm of Shabbat? This was the unresolved dilemma of the Sages, leading to their hesitation to include the verse describing Joseph’s labors in a foreign land.

(Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. III, pp. 7-9)

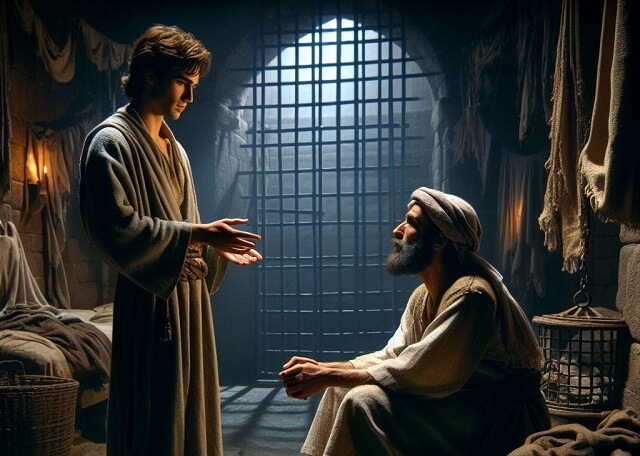

Illustration image: ‘Joseph as interpreter of dreams’ (Antonio Zanchi, 1631-1722)