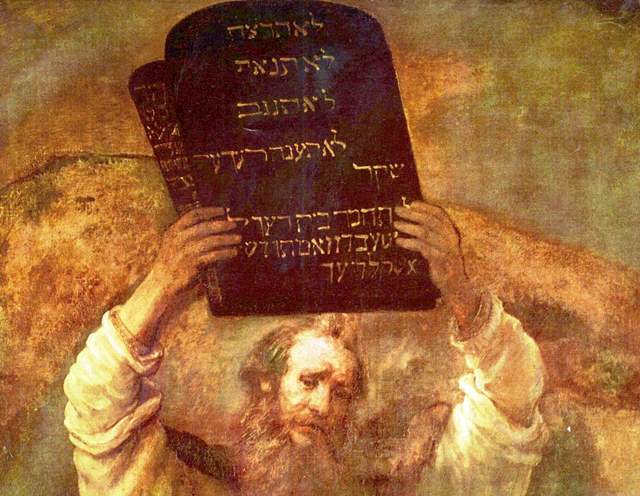

In the Torah reading of Mishpatim, the Torah makes an abrupt switch. The previous parashah of Yitro deals with great, universal topics: the Revelation at Sinai and the Aseret HaDibrot, the Ten Commandments.

From the heights of these lofty themes, the Torah

descends into the nitty gritty of everyday life.

Mishpatim deals with servants, thieves, and kidnappers. We read

about personal injury, damages, and negligence, and laws for

lending money and borrowing articles.

In short: Judaism is not just about fundamental beliefs and principles. The Torah’s ideals must permeate all aspects of life.

Lest one think that the two Torah portions are unrelated, the end of Mishpatim returns to the saga of Sinai, completing the account started in Yitro. At Sinai, God told Moses:

Come up to Me, to the mountain, and remain there. I will give you the stone tablets, the Torah and the mitzvah, that I have written for the people’s instruction. (Ex. 24:12)

What exactly are “the Torah and the mitzvah” that God promised to give Moses?

All from Sinai

Third-century scholar Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish explained that each term in the verse refers to a different component of Torah:

- “The stone tablets” refers to the Aseret HaDibrot.

- “The Torah” is the Five Books of Moses.

- “The mitzvah” is the Mishnah.

- “That I have written” refers to the Ketuvim (the ‘Writings,’ the third section of Tanakh).

- “For the people’s instruction” is the Talmud.

“This teaches that all of these were transmitted to Moses at Sinai.” (Berakhot 5a)

Clearly, Rabbi Shimon did not mean that everything was explicitly revealed to Moses. The Talmud in Menachot 29b relates that God showed Moses a vision of Rabbi Akiva, the renowned second-century scholar, lecturing to his students. Moses became distressed when he realized that he could not follow the lesson. Then one of the students asked Rabbi Akiva, “Our master, what is the source for this law?” The great scholar replied, “It is a law given to Moses at Sinai.” Upon hearing this, Moses was immediately relieved.

The specific case was unfamiliar to Moses. But Rabbi Akiva affirmed that its true, ultimate source was Mount Sinai.

The point of Rabbi Shimon’s exegesis is that the Oral Law — the Mishnah and the Talmud — are faithful applications of Sinaitic Law to the realities of life in second-century Eretz Yisrael and fifth-century Babylon. Not adjustments to the Torah to accommodate new times, but careful application of the guidelines set down at Sinai.

Tablets of Sapphire Stone

Rav Kook asked an interesting question: why were the Ten Commandments engraved on stone tablets? Why was it significant to mention the raw material used to make the tablets?

One might think that it is only necessary to be faithful to the spirit of the Torah — that is the essence of Judaism. The details, the specific rules of conduct, however, depend on the current culture and norms of society. They must be adapted to fit the needs of the day. In other words, we need not be overly concerned with the detailed legal code of Mishpatim. What is important is following the general spirit of Yitro.

Therefore, the Torah relates that the tablets were made of stone. According to the Midrash, it was not just any stone, but sapphire. This material was so tough that a hammer swung against them would be smashed to pieces. God used tablets made of unbreakable sapphire to emphasize that even the Torah’s physical manifestation — i.e., its day-to-day practical laws — may not be changed.

The concept of the Torah’s immutability, even in the details of everyday life, is particularly relevant to this verse. Sometimes the oral tradition appears to contradict the simple meaning of the written Torah. One might mistakenly think that the Talmudic sages adjusted Torah law to conform to the norms of their time. Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish taught that there are no changes in the Torah. The Mishnah and Talmud are rooted in oral traditions that go back to Mount Sinai. “All of these were transmitted to Moses at Sinai.”

(Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. I, p. 14)

Illustration image: ‘Moses with the Tablets of the Law’ (Rembrandt, 1659)