Azar’s Question

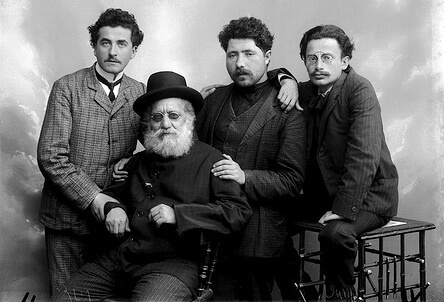

During the years that Rav Kook served as chief rabbi of Jaffa, he met and befriended many of the Hebrew writers and intellectuals of the time. His initial contact in that circle was the ‘elder’ of the Hebrew writers, Alexander Ziskind Rabinowitz, better known by the abbreviation Azar. Azar was one of the leaders of Po'alei Tzion, an anti-religious, Marxist party; but over the years, Azar developed strong ties with traditional Judaism. He met with Rav Kook many times, and they became close friends.

Azar once asked Rav Kook: How can the Sages interpret the verse “eye for an eye” (Ex. 21:24) as referring to monetary compensation? Does this explanation not contradict the peshat, the simple meaning of the verse?

The Talmud (Baba Kamma 84a) brings a number of proofs that the phrase “eye for an eye” cannot be taken literally. How, for example, could justice be served if the person who poked out his neighbor’s eyes was himself blind? Or what if one of the parties had only one functioning eye before the incident? Clearly, there are many cases in which such a punishment would be neither equitable nor just.

What bothered Azar was the blatant discrepancy between the simple reading of the verse and the Talmudic interpretation. If “eye for an eye” in fact means monetary compensation, why does the Torah not state that explicitly?

The Parable

Rav Kook responded by way of a parable. The Kabbalists, he explained, compared the Written Torah to a father and the Oral Torah to a mother. When parents discover their son has committed a grave offense, how do they react?

The father immediately raises his hand to punish his son. But the mother, full of compassion, rushes to stop him. “Please, not in anger!” she pleads, and she convinces the father to mete out a lighter punishment.

An onlooker might conclude that all this drama was superfluous. In the end, the boy did not receive corporal punishment. Why make a big show of it?

In fact, the scene provided an important educational lesson for the errant son. Even though he was only lightly disciplined, the son was made to understand that his actions deserved a much more severe punishment.

A Fitting Punishment

This is exactly the case when one individual injures another. The offender needs to understand the gravity of his actions. In practice, he only pays monetary restitution, as the Oral Law rules. But he should not think that with money alone he can repair the damage he inflicted. As Maimonides explained, the Torah’s intention is not that the court should actually injure him in the same way that he injured his neighbor, but rather “that it is fitting to amputate his limb or injure him, just as he did to the injured party” (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Personal Injuries 1:3).

Maimonides more fully developed the idea that monetary restitution alone cannot atone for physical damages in chapter 5:

“Causing bodily injury is not like causing monetary loss. One who causes monetary loss is exonerated as soon as he repays the damages. But if one injured his neighbor, even though he paid all five categories of monetary restitution — even if he offered to God all the rams of Nevayot [see Isaiah 60:7] — he is not exonerated until he has asked the injured party for forgiveness, and he agrees to forgive him.” (Personal Injuries, 5:9)

The Revealed and the Esoteric

Afterwards, Azar commented:

“Only Rav Kook could have given such an explanation, clarifying legal concepts in Jewish Law by way of Kabbalistic metaphors, for I once heard him say that the boundaries between Nigleh and Nistar, the exoteric and the esoteric areas of Torah, are not so rigid. For some people, Torah with Rashi’s commentary is an esoteric study; while for others, even a chapter in the Kabbalistic work Eitz Chayim belongs to the revealed part of Torah.”

Illustration image: Azar seated with Hebrew writers Shimoni, Brenner, and Agnon (Jaffa, 1910)

(Sapphire from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Malachim Kivnei Adam by Simcha Raz, pp. 351, 360.)