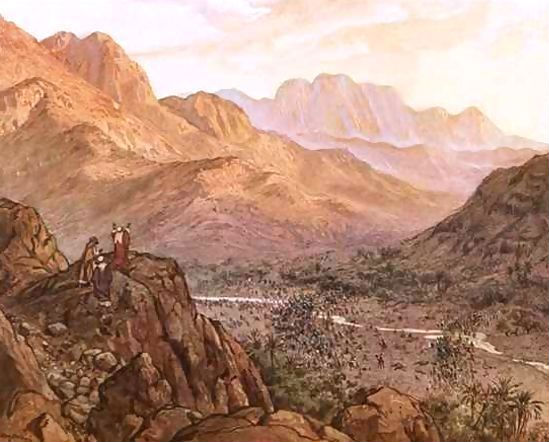

Amalek attacked the Israelites at Rephidim, intentionally targeting the weak and those lagging behind. Joshua engaged Amalek in battle, successfully defending Israel against this merciless enemy. Then God instructed Moses:

“Write this as a reminder in the book, and recite it in Joshua’s ears: I will completely obliterate the memory of Amalek from under the heavens.” (Exod. 17:14)

Why did God command Moses to write down His promise to obliterate Amalek in the Torah? And why did Joshua need to be told verbally? Couldn’t Joshua just read what was written in the Torah?

Two Missions

The people of Israel have two national missions. At Mount Sinai, God informed them that they would be a mamlechet kohanim (“kingdom of priests”) as well as a goy kadosh (“holy nation”) (Exod. 19:6). What is the difference between these two goals?

Mamlechet kohanim refers to the aspiration to uplift the entire world, so that all will recognize God. The people of Israel will fulfill this mission when they function as kohanim for the world, teaching them God’s ways.

But the Jewish people are not just a tool to elevate the rest of the world. They have their own intrinsic value, and they need to perfect themselves on their own special level. The central mission of Israel is to fulfill its spiritual potential and become a goy kadosh. If Israel’s sole function was to uplift the rest of the world, they would not have been commanded with mitzvot that isolate them from the other nations, such as the laws of kashrut and circumcision.

Two Torahs

God divided the Torah, our guide to fulfill our spiritual missions, into two components: the Written Law and the Oral Law. The written Torah was revealed to the entire world; all nations can access these teachings. God commanded that the Torah be written “in a clear script” (Deut. 27:8) — in seventy languages, so that it would be accessible to all peoples (Sotah 7:5). The Written Torah was meant to enlighten the entire world.

The Oral Law, on the other hand, belongs solely to the Jewish people. Since this part of Torah was not meant to be committed to writing, it is of a more concealed and less universal nature. In truth, the Oral Law is simply the received explanation of the Written Law, transmitted over the generations. Thus even the Written Torah is only fully accessible to Israel through the Oral Torah. But the other nations nevertheless merit a limited understanding of the Written Torah.

God’s Name and Throne

Amalek rejected both missions of Israel. Amalek cannot accept Israel as a mamlechet kohanim instructing the world, nor as a goy kadosh, separate from the other nations with its own unique spiritual aspirations. God promised to “completely obliterate” (macho emcheh) Amalek. In Hebrew, the verb is repeated, indicating that God will blot out both aspects of Amalek’s rejection of Israel.

Why did God command that His promise to destroy Amalek be written down and also transmitted orally? Since Amalek rejects Israel’s mission to elevate humanity, God commanded that His promise to obliterate Amalek be recorded in the Written Torah. The Written Law is, after all, the primary source of Israel’s moral influence on the world. And since Amalek also denies Israel’s unique spiritual heritage, God commanded that this promise be transmitted verbally, corresponding to the Oral Law, the exclusive Torah of Israel.

When Amalek has been utterly destroyed, the Jewish nation will be able to fulfill both of its missions. This is the significance of the statement of the Sages:

“God vowed that His Name and His Throne are not complete until Amalek’s name will be totally obliterated.” (Tanchuma Ki Teitzei 11; Rashi on Exod. 17:16)

What are “God’s Name” and “God’s Throne”? They are metaphors for Israel’s two missions: spreading knowledge of God — His Name — and creating a special dwelling place for God’s Presence in the world — His Throne. Amalek and its obstructionist worldview must be eradicated before these two goals can be accomplished.

(Silver from the Land of Israel, pp. 135-137. Adapted from Midbar Shur, pp. 312-316.)