An obvious question strikes anyone reading the last two portions of the book of Exodus: Vayakheil and Pekudei. Why was it necessary to repeat all of the details of how the Tabernacle was built? All of these matters were already described at great length in Terumah and Tetzaveh, which record God’s command to build the Mishkan.

The Command and the Execution

In several places, Rav Kook noted the divide in our lives between the path and the final goal.1 We tend to rush through life, chasing after goals — even worthwhile goals — with little regard for the path and the means. We see the path as a stepping stone, of no significance in its own right.

With these two sets of Torah portions Terumah-Tetzaveh and Vayakheil-Pekudei, we observe a similar divide. The first two record God’s command to build the Mishkan, while the second two document its actual construction. This is the distinction between study and action, between theory and practice. And it also corresponds to the aforementioned divide between means and ends.

Just as our world emphasizes goals at the expense of means, so, too, it values deed and accomplishment over thought and study. A more insightful perspective, however, finds a special significance in the path, in the abstract theory, in the initial command.

The Sages imparted a remarkable insight: “Great is Torah study, for it leads to action” (Kiddushin 40b). This statement teaches that Torah study — the theory, the path — is preferable to its apparent goal, the performance of mitzvot. Torah study leads us to good deeds; but it has an intrinsic worth above and beyond its value as a tool to know how to act.

The Talmud discusses whether a blessing should be recited when constructing a sukkah-booth. After all, the Torah commands us to build a sukkah — “The holiday of booths you shall make for yourselves” (Deut. 16:13). Nonetheless, the rabbis determined that no blessing is recited when building the sukkah, only when dwelling in it during the Succoth holiday. Why not?

Maimonides explained that when there is a command to construct an object for the purpose of fulfilling a mitzvah, one only recites a blessing on the final, ultimate mitzvah (see Hilchot Berakhot 11:8). Thus we do not recite a blessing when preparing tzitzit or when building a sukkah.

According to this line of reasoning, if Torah study were only a means to know how to keep mitzvot, no blessing would be recited over studying Torah. The fact that we do recite blessings over Torah study indicates that this study is a mitzvah in its own right, independent of its function as a preparation to fulfill other mitzvot.

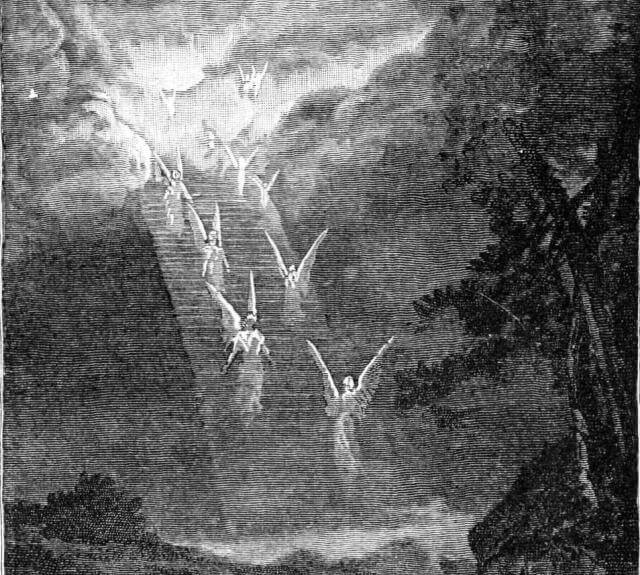

These two aspects of Torah — study and action — may be described as Divine influence traversing in opposite directions, like the angels in Jacob’s dream. The Torah’s fulfillment through practical mitzvot indicates a shefa that flows from above to below. This is the realization of God’s elevated will, ratzon Hashem, in the lower physical realm.

The intrinsic value of Torah study, on the other hand, indicates spiritual movement in the opposite direction. It ascends from below to above: our intellectual activity, without expression in the physical world; our Torah thoughts and ideas, without practical application.

Dual Purpose

The repetition in the account of the Mishkan reflects this dichotomy. The two sets of Torah readings are divided between command and execution, study and deed.

And on a deeper level, the repetition reflects the dual function of the Mishkan (and later on, the Temple). On the practical level, the Mishkan was a central location for offering korbanot to God. It served as a center dedicated to holy actions.

But on the abstract, metaphysical level, the Mishkan was a focal point for God’s Presence, a dwelling place for His Shekhinah.

They shall make for Me a Temple, and I will dwell (ve-shekhanti) among them (Ex. 25:8).

Like the diametric influences of Torah, one descending and one ascending, each of the Tabernacle’s functions indicated an opposite direction. Its construction, the dedication of physical materials to holy purposes, and the offering of korbanot to God, flowed upwards. An ascent from the physical world below to the heavens above.

The indwelling of the Shekhinah, on the other hand, was a descending phenomenon from above to below, as God’s Divine Presence resided in the physical universe, a source of divine inspiration and prophecy.

(Adapted from Shemuot HaRe’iyah, Vayakheil-Pekudei (1931))

1 For example, _Orot_ _HaTeshuvah_ 6:7; _Mo'adei_ _HaRe’iyah_, p. 110.