Rabbi She'ar Yashuv Cohen, Chief Rabbi of Haifa and son of the Rav HaNazir, told the story of his part in defending Jerusalem during the 1948 War of Independence:

During the winter of 5708 (1947-1948), I was one of the younger students at the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva. I was also a member of the Haganah, the pre-state Jewish defense organization. This was during the period of Arab rioting and attacks that erupted following the United Nations’ vote on the 29th of November, 1947, to establish a Jewish state.

In those days, there was much discussion in Mercaz HaRav whether the yeshiva students should enlist and take part in the defense efforts. Both my father, the Rav HaNazir, and Rav Tzvi Yehudah were of the opinion that everyone is obligated to go out and fight. This was a milhemet mitzvah, a compulsory war in which all are expected to participate.

However, those close to the head of the yeshiva, Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Charlap, argued that yeshiva students should continue their Torah studies in the yeshiva, and the merit of their Torah learning would secure victory in battle. They would quote the verse in Isaiah 62:6, “On your walls, Jerusalem, I have posted watchmen,” explaining that these watchmen protecting the city are in fact scholars, diligent in their Torah study.

At that time, the situation in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City was desperate. I came up with the idea of organizing a group of yeshiva students to establish a “Fighting-Defense Yeshiva” in the Jewish Quarter. The yeshiva’s daily schedule would be comprised of eight hours for defense and guard duty, eight hours for Torah study, and the remaining eight hours for rest and sleep.

The proposal was presented to the Haganah command and received their approval. However, individuals associated with Rabbi Charlap were vehemently opposed to the idea. The controversy within Mercaz HaRav disturbed me deeply and caused me great anguish.

One day, as I exited the yeshiva, I saw huge notices posted at the entrance to the yeshiva. It was a broadside quoting Rav Abraham Isaac Kook, of blessed memory, that yeshiva students should not be drafted into the army. When I read the notices, I was in shock. Was I acting against the teachings of our master, Rav Kook?

Agitated and upset, I made my way down the road toward Jerusalem’s Zion Square. There I saw a figure walking toward me, slightly limping. As he came closer, I saw that it was Rav Tzvi Yehudah. I felt very close to Rav Tzvi Yehudah; he was like an uncle to me.

When he saw my shocked face, Rav Tzvi Yehudah became concerned. “What happened, She'ar Yashuv? Why do you look like that? Don’t be afraid. Tell me!”

Under the pressure of his questioning, I told him about my efforts to organize a “fighting yeshiva” in the Jewish Quarter, and my distress when I saw the posters that indicated we were acting against his father’s guidance.

When he heard my words, Rav Tzvi Yehudah was horrified. He grabbed me by the shoulders and thundered, “This is an outright forgery! A distortion and utter falsehood!” He was so upset, his shouts reverberated down the street.

After regaining his composure, he explained that the notices were quoting a letter his father had written during the First World War while he was in London. The letter dealt with the conscription of yeshiva students who had escaped from Russia to England. Rav Kook argued that these students should be exempt from the draft, just like other religious clergy students who were granted exemptions by the British authorities.

“But here,” Rav Tzvi Yehudah gestured emphatically with his hands, “here we are fighting for our hold on the Land of Israel and the holy city of Jerusalem. This is undoubtedly a milhemet mitzvah; whereas in England, the demand was that the yeshiva students fight for a foreign army.”

The rabbi’s words reassured me. I asked if he would be willing to write them down so that they could be publicized, and he consented. The rabbi proceeded to publicize a broadside in which he objected to the use of his father’s letter to Rabbi Hertz, Chief Rabbi of England, during World War I.

I also asked Rav Tzvi Yehudah to publish his views on the matter in a more detailed and reasoned format. He replied that there is no point in composing an article when the city is under siege and the printing presses are closed down. However, I managed to obtain a special permit from the Defense Board, so that a pamphlet containing five articles on the subject was published shortly thereafter.

In his article, Rav Tzvi Yehudah explained that joining the army at that time was important for three reasons:

“God’s redeemed will return”

Even though I was the one who had initiated the pamphlet’s publication, I did not receive a copy when it was printed. Due to special circumstances, several months passed before I received a copy.

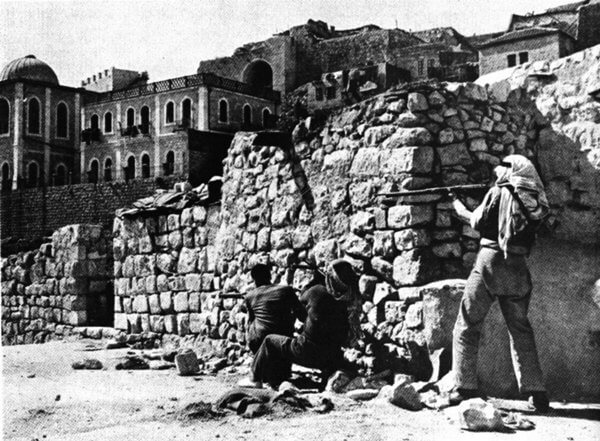

I was one of the volunteers who succeeded in finding a way to slip inside the walls of the Old City. I joined the fighters there, and I was seriously wounded in battle.

When the Old City fell to the Arab Legion on May 27th, 1948, I was taken prisoner. The Jordanian commander was shocked to discover that only 26 of the surrendering Jewish soldiers survived the battles without serious injury. Embarrassed to return victorious to Jordan with such a small contingent of prisoners, he decided to also take wounded soldiers.

After seven months as a prisoner in Jordan, we were repatriated to Israel in a prisoner exchange deal. I was taken to Zichron Ya’akov to recuperate, and Rav Tzvi Yehudah came to visit me the first morning after my arrival.

The morning of Rav Tzvi Yehudah’s visit, as I was removing my tefillin after morning prayers, I peered out the window and saw Rav Tzvi Yehudah slowly making his way up the mountain. Afterward, I found out that he had taken the very first bus from Jerusalem, and had traveled early in the morning all the way to Zichron Ya’akov to greet me.

I ran toward him, and he hugged and kissed me. He cried over me like a child. The truth is that my situation was so grave that my family and friends had nearly relinquished all hope. Until then, such a thing had never happened — returning alive from captivity in an Arab country. But the Jordanian King Abdullah had wanted to show the world that he was an enlightened monarch who respected international law....

After recovering from his outburst of emotion, Rav Tzvi Yehudah reached into his coat pocket and brought out a small pamphlet containing his article about defending the country. Inside was a personal inscription:

“For my dear beloved friend — the initiator, advisor, and solicitor [of this tract]. This pamphlet is set aside, from the day it was printed, until ‘God’s redeemed will return in peace, and joyfully come to Zion.'”

Decades later, I still have that treasured pamphlet carefully stored in my possession.

(Stories from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Mashmia Yeshuah, pp. 270-272)