Crossing the Jordan River

On the banks of the Red Sea, with Egyptian slavery behind them, the Israelites triumphantly sang Shirat HaYam. This beautiful “Song of the Sea” concludes with a vision of a future crossing into freedom and independence — across the Jordan River, to enter the Land of Israel.

עַד־יַעֲבֹר עַמְּךָ ה’

-

עַד־יַעֲבֹר עַם־זוּ קָנִיתָ׃

“Until Your people have crossed, O God; until the people that You acquired have crossed over.” (Exod. 15:16)

Why the repetition — “until Your people have crossed,” “until the people... have crossed over”?

The Talmud (Berachot 4a) explains that the Jewish people crossed the Jordan River twice. The first crossing occurred in the time of Joshua, as the Israelites conquered the Land of Israel from the Canaanite nations. This event marked the beginning of the First Temple period.

The second crossing took place centuries later, when Ezra led the return from Babylonian exile, inaugurating the Second Temple period.

The verse then refers to both crossings. In what way does each phrase relate to its specific historical context?

Two Forms of Holiness

Rav Kook wrote that the Jewish people possess two aspects of holiness. The first is an inner force that resides naturally in the soul. This trait is a spiritual inheritance passed down from the patriarchs, which Rav Kook referred to as an innate “segulah-holiness.” It is an intrinsic part of the Jewish soul, and is immutable.

The second aspect of holiness is based on our efforts and choices. Rav Kook called this “willed-holiness,” as it is acquired consciously, through our actions and Torah study. Innate-holiness is in fact infinitely greater than willed-holiness, but it is only revealed to the outside world according to the measure of acquired holiness. It is difficult to perceive an individual’s inner sanctity when it is not expressed in external actions or character traits.

Each of the two eras in Jewish history, the First and Second Temple periods, exemplified a different type of holiness.

The First Temple period commenced with Joshua leading the people across the Jordan River. The people of Israel at that time were characterized by a high level of intrinsic holiness. The Shechinah, God’s Divine Presence, was openly revealed in the Temple, and miracles occurred there on a constant basis. It was an era of prophecy, and books were still being added to Scripture. This period corresponds to the phrase, “until Your people have crossed, O God.” The expression “Your people” emphasizes their inherent connection to God, i.e., the aspect of innate-holiness.

The return to Zion in the time of Ezra marked the beginning of the Second Temple period. The Second Temple did not benefit from the same miraculous phenomena as the First Temple. Prophecy ceased, and the canonization of Scripture was complete.

However, the willed-holiness of that era was very great. The Oral Law flourished, the Mishnah was compiled, and new rabbinical decrees were established. This period corresponds to the second phrase, “until the people that You acquired.” The main thrust of their connection to God was willed-holiness, acquired through good deeds and Torah study.

The Generation Preceding the Messiah

The Rabbi of Safed, Rabbi Jacob David Willowsky (known by the acronym the “Ridbaz”), criticized Rav Kook for his congenial relations with the non-religious (and often anti-religious) pioneers who were settling the Land of Israel. Rav Kook responded to this criticism by noting the distinction between different forms of holiness.

“In our generation, there are many souls who are on a very low level with regard to their willed-holiness. Thus, they are afflicted with immoral behavior and dreadful beliefs. But their innate segulah light shines brightly. That is why they so dearly love the Jewish people and the Land of Israel.” (Igrot HaRe’iyah vol. II, letter 555 (1913), pp. 187-188)

Rav Kook went on to explain that heretics and non-believers usually lose their inner segulah holiness, and separate themselves from the Jewish people. However, we live in special times. The Zohar describes the pre-Messianic generation as being “good on the inside and bad on the outside.” That is to say, they have powerful inner holiness, even though their external, acquired holiness is weak and undeveloped. They are the allegorical “donkey of the Messiah” (see Zechariah 9:9), as the donkey bears both external signs of impurity, but nonetheless, contains an inner sanctity, as evidenced by the fact that firstborn donkeys are sanctified as bechorot (Exod. 13:13).

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp, 124-126. Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. I, p. 236)

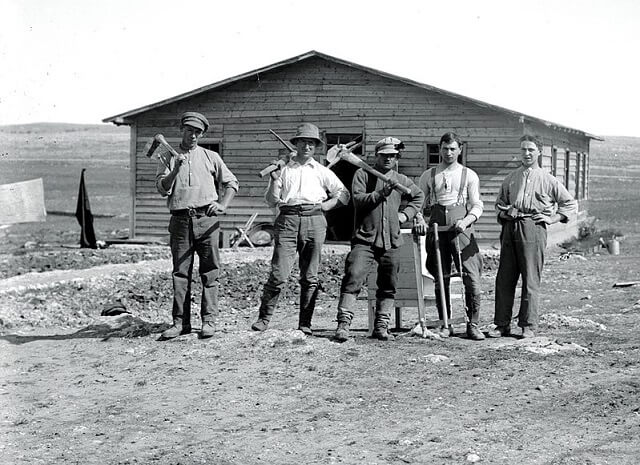

Illustration image: ‘Commencing a Jewish settlement’ (American Colony, Jerusalem, 1920-1930)