The treacherous attack of Amalek, striking against the weak and helpless, was not a one-time enmity, a grievance from our distant past. God commanded Moses to transmit the legacy of our struggle against Amalek for all generations:

“God told Moses, ‘Write this as a reminder in the Book, and repeat it in Joshua’s ears: I will totally obliterate the memory of Amalek from under the heavens....’ God will be at war with Amalek for all generations.” (Exod. 17:14, 16)

Erasable Writing

The evil of Amalek invaded every aspect of the universe. Even holy frameworks were not immune to this defiling influence. Therefore, they too require the possibility to be repaired by erasing, if necessary.

For this reason, the Talmud (Sotah 17b; see Yoreh Dei'ah 271:6) rules that scribes should not add calcanthum (vitriol or sulfuric acid) to their ink, since calcanthum-enhanced ink cannot be erased by rubbing or washing. All writing — even holy books — must have the potential to be erased, as they may have been tainted by sparks of evil.

An extreme example of a holy object that has been totally contaminated is a Torah scroll written by a heretic. In such a case, it must be completely burned by fire (Shabbat 116a; Yoreh Dei'ah 281:1). Usually, however, holy objects only come in light contact with evil, and it is sufficient to ensure that the scribal ink is not permanent, so that the writing has the potential to be erased.

The Unique Torah of Rabbi Meir

However, we find one scribe who did add calcanthum to his ink: the second-century scholar Rabbi Meir. Rabbi Meir was a unique individual. The Talmud states that there was none equal to Rabbi Meir in his generation. His teachings were so extraordinary that his colleagues were unable to fully follow his reasoning. Because of Rabbi Meir’s exceptional brilliance, the Sages were afraid to rule according to his opinion (Eiruvin 13a-b).

The Talmud further relates that Rabbi Meir’s true name was not Meir. He was called Meir because “he would enlighten (me'ir) the eyes of the Sages in Halachah.” What made Rabbi Meir’s approach to Torah so unique? His teachings flowed from his aspiration to attain the future enlightenment of the Messianic Era. Because of this spiritual connection to the Messianic Era, the Jerusalem Talmud (Kilayim 9:3) conferred upon him the title “your messiah.”

Rabbi Meir had no need to avoid using calcanthum, since his Torah belonged to the future era when Amalek’s evil will be eradicated. On the contrary, he took care to enhance his ink, reflecting the eternal nature of his lofty teachings.

Rabbi Akiva, on the other hand, taught that scribes should not avail themselves of calcanthum. In the world’s current state, everything must have the potential to be erased and corrected, even that which contains holy content. Only in this way will we succeed in totally obliterating Amalek and his malignant influence. Then we will halt the spread of evil traits in all peoples, the source of all private and public tragedy.

Uniting the Oral and Written Law

The influence of Amalek had a second detrimental effect on the Torah. God commanded Moses to communicate the struggle against Amalek in two distinct channels. Moses transmitted God’s message in writing - “Write this in the Book” — and orally — “Repeat it in Joshua’s ears.” The refraction into divergent modes of transmission indicated that the Torah had lost some of its original unity.

Consequently, the Talmud rules that a scribe may not write from memory, not even a single letter (Megillah 18b). Our world maintains an entrenched division between the written and spoken word. Only with the obliteration of Amalek and the redemption of the world will we merit the unified light of the Torah’s oral and written sides.

Once again, we find that Rabbi Meir and his Torah belonged to the future age, when this artificial split will no longer exist. Thus, when Rabbi Meir found himself in a place with no books, he wrote down the entire book of Esther from memory.

In the time of Mordechai and Esther, when we gained an additional measure of obliterating Amalek (with the defeat of Haman, a descendant of Amalek), the Torah regained some of its original unity. That generation accepted upon itself the Oral Law, in the same way that the Written Law had been accepted at Sinai (Shabbat 88a).

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 127-129. Adapted from Igrot HaRe’iyah vol. III, pp. 86-87 (1917).)

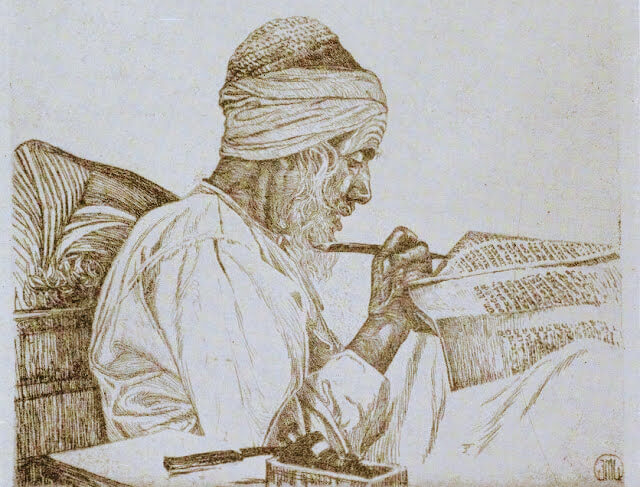

Illustration image: ‘Der Torahschreiber’ (Ephraim Moses Lilien, 1914)